Gabrielle Lawrence is a PhD Candidate at the Australian National University, Australia. Her research explores the role of lived experience knowledge in social security policy-making in Australia. Gabrielle commenced her PhD after 18 years in the Australian Public Service (APS) and her research responds to identified challenges facing the APS – growing public expectations for more inclusive policy processes and the need for more diversified forms of evidence to address complex policy challenges. Gabrielle is gratefully assisted by her supervisor Professor Janine O’Flynn and associate supervisors Dr Liz Allen, Dr Katie Curchin and Dr Colette Einfeld.

As a policy practitioner, I had been grappling with a persistent question: why do some voices get heard in policy making processes while others remain systematically silenced? I came to my PhD wanting to understand why lived experience knowledge was conspicuously absent in Australian social security and unemployment policy making.

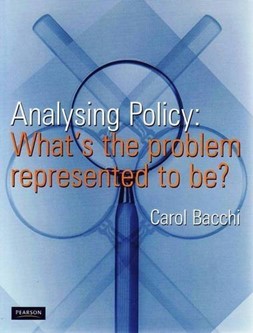

I discovered the What’s the Problem Represented to be? (WPR) (Bacchi 2009) approach at a PhD colleague’s final thesis presentation. Still fumbling with conceptual frameworks in my first year, I watched as she applied this questioning framework to show how well-meaning education policies were perpetuating harmful assumptions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ academic capacity. It was a light-bulb moment.

As a practitioner-researcher, I wanted my research to offer tangible and practical findings that could lead to real change. But my research ambition – to offer findings that could help disrupt established knowledge hierarchies – felt anything but tangible.

However, WPR offered me a concrete framework for examining what felt like hard-to-pinpoint strategic relations, shifting analytic attention beyond amorphous discourses and political narratives to the policy instruments themselves – how they construct the problems and the people they claim to serve.

Applying WPR’s questions to 30 years of welfare reform documents revealed how policy consistently represents unemployment as moral failure, positioning income support recipients as “irresponsible” or “incapable” citizens. This rests on deep assumptions: individuals are to blame, government knows best, and paid work is always the solution.

WPR’s power lies in exposing what’s left unproblematic. While policy obsesses over individual behaviour, it remains silent about structural unemployment, job quality, discrimination, and unpaid care work.

Most striking was how policy creates particular identities: the deficit identity of the income support recipient, defined primarily by lack of paid employment and the morally superior policy actors which must paternalistically ‘save’ recipients from themselves. These constructed identities explain recipients’ exclusion—if positioned as deficit subjects requiring intervention, why would their knowledge be valuable?

As a practitioner-researcher, I’ve encountered challenges applying WPR in bureaucratic contexts. Its post-structuralist foundations seem opposed to conventional policy epistemologies, and its language can be confronting for policy audiences.

Yet WPR’s disruptive potential is precisely its value. It locates the source of knowledge delegitimisation, helping advocates target change strategies and offering policy actors a framework for recognising embedded hierarchies.

WPR points us towards transformation. By bringing visibility to counter-narratives and challenging taken-for-granted assumptions, we can disrupt established practices and create space for genuinely inclusive policy making that centres lived experience. For fellow practitioner-researchers, WPR offers both analytical rigor and practical pathways for change – exactly what we need to challenge entrenched knowledge hierarchies in public policy.

Leave a comment